Five Main styles of Chinese character calligraphy art

The are five main styles in Chinese Calligrahy art. They are small seal scipt/ style, official/clerical script, Semi-cursive script (Running Script), Cursive script (Grass Script), and Formal/Regular Script (Standard Script).

From the seal script was derived the clerical script; and from the clerical script were derived both the regular script and the cursive scripts.

Characters are often written in ancient variations or simplifications that deviate from the modern standards used in Chinese, Japanese, or Korean. Modern variations or simplifications of characters, akin to Chinese Simplified characters or Japanese shinjitai, are occasionally used, especially since some simplified forms derive from cursive script shapes in the first place.

The Japanese syllabaries of katakana and hiragana are used in calligraphy; katakana were derived from regular script shapes and hiragana from characters in the cursive script. In Korea, the post-Korean War period saw the increased use of hangul, the Korean alphabet, in calligraphy.

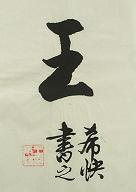

Seal Script

The Seal Script (often called Small Seal Script) is the formal script of the Qin system of writing, the informal script of which was precursor to the Clerical Script. Seal script is the oldest style that continues to be widely practiced. Today, this ancient style of Chinese writing is used predominantly in seals, hence the English name. Although seals (name chops), which make a signature-like impression, are carved in wood, jade and other materials, the script itself was originally written with brush and ink on paper, just like all other scripts.

Most people today cannot read the seal script, so it is generally not used outside the fields of calligraphy and carved seals. However, because seals act like legal signatures in Chinese culture, Korean culture, and Japanese culture, and because vermillion seal impressions are a fundamental part of the presentation of works of art such as calligraphy and painting, seals and therefore seal script remain ubiquitous. ( more about seal script... )

Clerical/Official Script

The Clerical Script (often simply termed lìshū; and sometimes called Official, Draft or Scribal Script) developed from the Seal Script. In general, characters are often "flat" in appearance, being wider than they are tall. The strokes may appear curved and with variations in width. Most noticeable is the dramatically flared tail of one dominant horizontal or downward-diagonal stroke, especially that to the lower right. This characteristic stroke has famously been called 'silkworm head and wild goose tail' (蠶頭雁尾 cántóu yànwěi)in Chinese due to its distinctive shape.

The archaic Clerical Script of the Chinese Warring States period to Qin Dynasty and early Han Dynasty can often be difficult to read for a modern East Asian person, but the mature Clerical Script of the middle to late Han dynasty is generally legible. Modern works in the Clerical Script tend to use the mature, late Hàn style, and may also use modernized character structures, resulting in a form as transparent and legible as Regular (or standard) Script. The Clerical Script remains common as a typeface used for decorative purposes (for example, in displays), but it is not commonly written. (More about Clerical Style ... )

Semi-cursive Script

The Semi-cursive Script (also called Running Script, 行書) approximates normal handwriting in which strokes and, more rarely, characters are allowed to run into one another. In writing in the Semi-cursive Script, the brush leaves the paper less often than in the Regular Script. Characters appear less angular and rounder.

In general, an educated person in China or Japan can read characters written in the Semi-cursive Script with relative ease, but may have occasional difficulties with certain idiosyncratic shapes. ( More about Semi-cursive Style ... )

Cursive Script

The Cursive Script (sometimes called Grass Script, 草書) is a fully cursive script, and a person who can read the Semi-cursive Script cannot be expected to read the Grass Script without training. Entire characters may be written without lifting the brush from the paper at all, and characters frequently flow into one another. Strokes are modified or eliminated completely to facilitate smooth writing and to create a beautiful, abstract appearance. Characters are highly rounded and soft in appearance, with a noticeable lack of angular lines.

The Cursive Script is the source of Japanese hiragana, as well as many modern simplified forms in Simplified Chinese characters and Japanese shinjitai. ( More about Cursive Style.. )

Regular Script

The Regular Script (often called standard script or simply kǎishū) is one of the last major calligraphic styles to develop, emerging between the Chinese Han dynasty and Three Kingdoms period, gaining dominance in the Southern and Northern Dynasties, and maturing in the Tang Dynasty. It emerged from a neatly written, early period semi-cursive form of clerical script. As the name suggests, the Regular Script is "regular", with each of the strokes placed slowly and carefully, the brush lifted from the paper and all the strokes distinct from each other.

The Regular Script is also the most easily and widely recognized style, as it is the script to which children in East Asian countries and beginners of East Asian languages are first introduced. For learners of calligraphy, the Regular Script is usually studied first to give students a feel for correct placement and balance, as well as to provide a proper base for the other, more flowing styles.

In the Regular Script samples to the right, the characters in the left column are in Traditional Chinese while those to the right are in Simplified Chinese. ( More about Regular Script... )

![]() This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article "Wikipedia".

This article is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License. It uses material from the Wikipedia article "Wikipedia".